Miscellanies about Heisenberg and Beethoven

... one should not forget that whatever one’s achievements in identifying a “classical realm” in quantum mechanics, the theory continues to incorporate another realm, the pure quantum world, that the young Heisenberg first gained access to, if not through his mathematics, then perhaps through the music of his favourite composer, Beethoven. This world beyond ken has never been better described than by Hoffmann (Musikalische Novellen und Aufsätze. Leipzig: Insel-Bücherei 1810) in his essay on Beethoven’s instrumental music, and we find it appropriate to end this paper by quoting at some length from it [Translation copyright: Ingrid Schwaegermann (2001)]...Beethoven’s instrumental music opens to us the realm of the gigantic and unfathomable. Glowing rays of light shoot through the dark night of this realm, and we see gigantic shadows swaying back and forth, encircling us closer and closer, destroying us (. . . ) Beethoven’s music moves the levers of fear, of shudder, of horror, of pain and thus awakens that infinite longing that is the essence of romanticism...Only that composer truly penetrates into the secrets of harmony who is able to have an effect on human emotions through them; to him, relationships of numbers, which, to the Grammarian, must remain dead and stiff mathematical examples without genius, are magic potions from which he lets a miraculous world emerge.

(Submitted on 10 Jun 2005 (v1), last revised 25 Jul 2005 (this version, v2))

An account was recently given me of an episode that occurred when Heisenberg was visiting Cambridge University. The discoverer of the principle of indeterminacy is a gifted amateur pianist. One evening after dinner in hall with the fellows of a college, he was persuaded to sit down at the instrument. He played the last sonata of Beethoven, opus 111. He finished amid silence produced by the majesty of the music. “There, gentlemen,” he remarked, “you have the difference between science and art. If I had never lived, another would have discovered the principle of indeterminacy. Given the evolution of science the discovery was inevitable. But if Beethoven had never lived, no one would have written that sonata”

The United States and CivilizationNef John U.(2nd ed. rev. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967. p83-84)

Heisenberg ... had never viewed music as a means to become fully emotionally expressive in order to then return to life - after a somewhat Aristotelian catharsis,- full of new strength and cleansed. Rather, it meant to him, much like mathematics, a passageway to gain knowledge of what he termed the central order... Throughout his life, he saw himself confronted with the task of gaining access to the knowledge of reality, which understands the various connections as components of a single, meaningfully ordered world.(31) A first attempt at gathering these thoughts is made in the text Reality and its Order from the year 1942. Here he is fully mindful throughout that language is ultimately inadequate: The ability of man to understand is limitless. Of the ultimate things one cannot speak.(32)

During the early forties, in a strange coincidence, the thoughts of both Heisenberg and Thomas Mann are circling around the last composition of Beethoven, his Piano Sonata op. 111 with its simple, slow movement with variations. Thomas Mann.... describes it - half ironically, half seriously- as surmounting a tradition that had already reached its pinnacle and talks of passages of melodic delight by which the turbulent stormy sky of the piece is periodically lit as if by tender rays of light (Doktor Faustus, op. cit. pp.71).

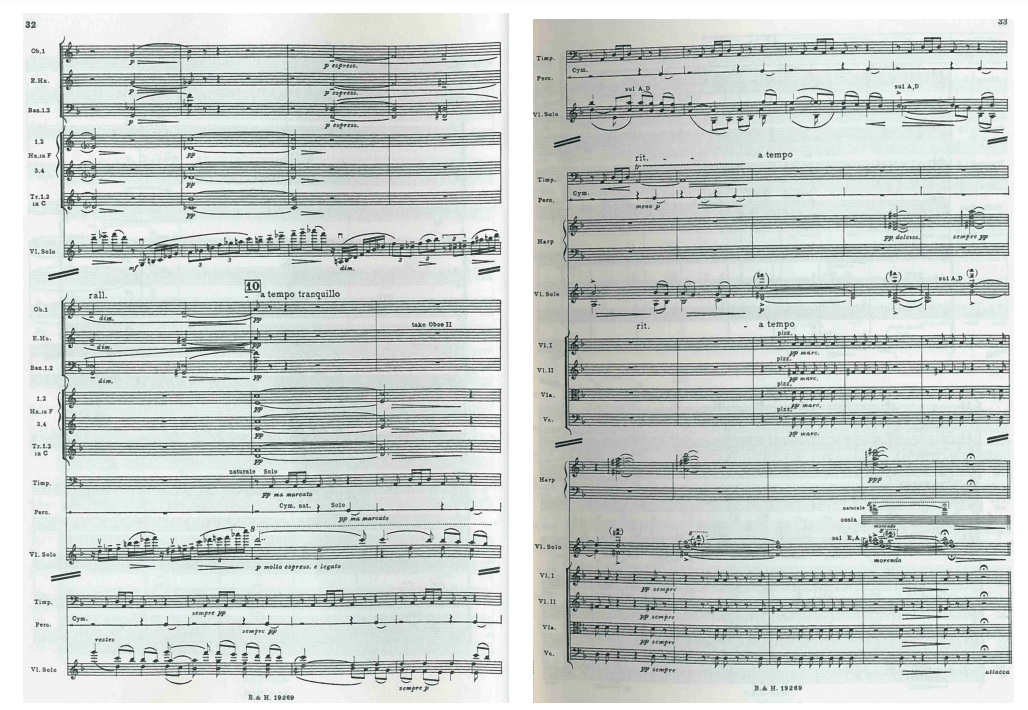

Most likely, these rays of light are the reason Heisenberg incorporated the score of such a passage into his text on reality and its order. It denotes the first bars of the variations movement, the Arietta theme Adagio molto, semplice e cantabile...

Heisenberg... is attempting in his writing from 1942 to decipher reality and its order through a systematic approach and a critical accuracy of language. The Arietta-theme serves him here as an example for those totally pure entities of the mind that are detached from everything earthly (Ordnung der Wirklichkeit op. cit p.301) which could only be created by those blessed humans who have access to the creative forces of the soul.

In contrast to Thomas Mann, he does not use a lot of words on this musical theme, because he is unable to speak about the final things. In their stead music itself has to speak, even if only through the image of a score. If this were a conversation with my father, now would be the moment he would probably walk over to the piano, sit down and, gazing thoughtfully across the music stand, express through the sounds of the music what he meant.

HEISENBERG AND MUSIC

Barbara Blum.

Translation: Irene Heisenberg

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire

Cher-ère lecteur-trice, le blogueur espère que ce billet vous a sinon interessé-e du moins interpellé-e donc, si le coeur vous en dit, osez partager avec les autres internautes comme moi vos commentaires éclairés !

Dear reader, the blogger hopes you have been interested by his post or notice something (ir)relevant, then if you are in the mood, do not hesitate to share with other internauts like me your enlightened opinion !